- Over 200 IDPs in Ponnagyun struggle without shelter, food aid

- Junta airstrikes inflict deep psychological trauma on children in Arakan State

- Photo News: Over 200 IDPs in Ponnagyun in urgent need of shelter assistance

- Two children injured by UXO in Mrauk-U struggle to afford medical care

- High hepatitis cases hit children in Arakan State

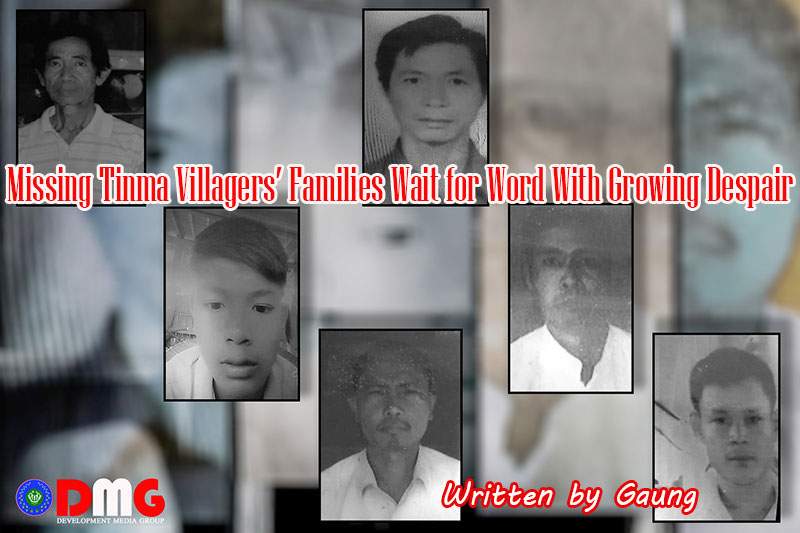

Missing Tinma Villagers’ Families Wait for Word With Growing Despair

The remaining Tinma villagers could not accept that reply, saying their relatives were abducted before their very eyes.

28 Oct 2022

Written by Gaung

Daw San Aye Than and her family fled their home after her husband was detained by the Myanmar military more than two years ago. They are now sheltering at a displacement camp beside a railway station in Arakan State’s Kyauktaw, still living in hopes that he will someday be released.

“Myanmar military soldiers said they would do nothing to my husband, and that he would be released the following day. However, he has never been released,” Daw San Aye Than said with frustration.

In March 2020, Myanmar military soldiers based at Mt. Taung Shae, near Tinma Village and the shores of the Kaladan River in northern Kyauktaw Township, entered Tinma Village, firing guns and ultimately arresting 18 villagers.

U Than Maung Tun, the husband of Daw San Aye Than, was one of the detainees. It has been more than two-and-a-half years since his abduction.

U Than Maung Tun was having lunch with his family when he was taken from his home to the military outpost at Mt. Taung Shae, reportedly being tied and beaten by soldiers along the way.

When Daw San Aye Than asked the soldiers why they were abducting her husband, the soldiers threatened to kill her. Family members describe U Than Maung Tun, 46, as an ordinary family man who farms and collects firewood to make a living.

“My husband is a quiet man, and does not have any quarrel with anyone. All villagers and neighbours know that,” said Daw San Aye Than, who has been struggling to make ends meet at the displacement camp, with five family members including her paralysed father-in-law to feed and care for. Her father-in-law has only been treated with traditional medicine, and she has had to borrow money to buy medicines for him as cash contributions that she receives from individual donors are not enough.

U Maung Seikkyi, a 72-year-old man from new Tinma Village, was also detained in March 2020, along with U Than Maung Tun and other villagers.

“No one has yet been released, and I haven’t heard anything about my father since then,” said Ma May Chay Win, a daughter of U Maung Seikkyi.

Family members are concerned about his health as he is overweight and suffers from high blood pressure.

Ma May Chay Win also lives in the IDP camp at the Kyauktaw railway station, together with her ailing mother, children and a niece. Her 69-year-old mother suffers from chronic hypertension, eye problems and a broken hip.

Family members have sought the help of local ex-lawmakers and the Arakan Human Rights Defenders and Promoters Association, but to no avail thus far.

They filed complaints to the State Counsellor, Myanmar National Human Rights Commission and the Office of Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services in March 2020. In October of that year, the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission responded, saying none of the 18 villagers were in military custody.

“They replied that there was no such abduction by the Myanmar military,” said U Myat Tun, director of the Arakan Human Rights Defenders and Promoters Association, who helped the detainees’ families file complaints with authorities. “This is the Myanmar military’s blatant violation of human rights.”

The remaining Tinma villagers could not accept that reply, saying their relatives were abducted before their very eyes.

A veteran lawyer from Arakan State who asked for anonymity said: “Military leaders have to give commanders on the ground punishment proportional to the crimes that they have committed. This case is the crime of murder and disposing corpses. The perpetrators must be held accountable under both military law and civilian law.”

Among the detainees were teenage students and disabled people, as well as elderly people over 60 years of age. Arakanese lawyers have said that such an act, if true, amounts to a war crime.

DMG attempted to contact regime spokesman Major-General Zaw Min Tun regarding the matter, but he could not be reached.

Family members tried to file a case with the military at the Kyauktaw Myoma police station twice, in March and December of that year, but police refused to accept the case, saying it was related to the military.

An investigation team was formed in January 2021 with the cooperation of village elders, and included the district police force chief and head of the township police force, to probe the disappearance of the Tinma villagers.

The investigation team summoned family members of each of the detainees and took their statements. The family members unanimously said the Tinma villagers were abducted by members of the military’s Light Infantry Division No. 55.

“We were asked some questions such as: ‘Who saw the detention of the Tinma villagers? When were they arrested?’ We were also given words of encouragement, but nothing has been significant so far,” said Ma May Chay Win.

Women’s rights activists have been vocal in criticising authorities’ handling of the case.

“Concerned officials have completely ignored the disappearance of the Tinma villagers, making it a challenge for their families, especially women, to stay in an insecure area for livelihood,” said Saw San Nyein Thu, chairwoman of the Rakhine Women’s Initiative Organisation (RWIO). She added that since the detainees are all men, family members who once depended on them have faced livelihood struggles in the years since they were arrested.

Women’s rights activists have pointed out that the armed forces must act in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution No. 1325 on women’s peace and security for victims of violence.

“What we say applies, no matter how long the war is. During that time, there must be plans to protect children and women. Both armies must follow the rules,” said Saw San Nyein Thu.

Regardless of the detainees’ ultimate fate, the Arakan Human Rights Defenders and Promoters Association says the mere process by which the Tinma villagers were detained and the authorities’ subsequent handling of the case are examples of egregious human rights violations.

For the time being, five family members live huddled together in a small shack made of bamboo, hoping for the return of a loved one.

“If they’d died in front of my eyes, I might have been able to console them,” said Daw San Aye Than, sobbing. “I don’t think they’re dead yet, but I hope they’ll come home one day.”

.jpg)