- Over 200 IDPs in Ponnagyun struggle without shelter, food aid

- Junta airstrikes inflict deep psychological trauma on children in Arakan State

- Photo News: Over 200 IDPs in Ponnagyun in urgent need of shelter assistance

- Two children injured by UXO in Mrauk-U struggle to afford medical care

- High hepatitis cases hit children in Arakan State

Landmines Responsible for Ongoing Series of Shattered Lives in Rural Arakan

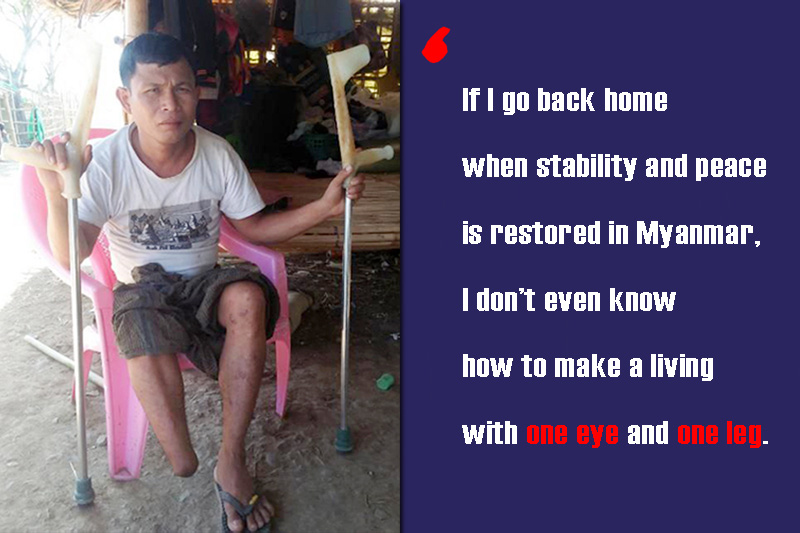

“If I go back home when stability and peace is restored in Myanmar, I don’t even know how to make a living with one eye and one leg,”

08 May 2023

Written by May Gyi Shin

With a loud explosion from the ground, U Ba Shwe tumbled over. He was conscious and aware that he had stepped on a landmine. So, he checked over his body to find that the mine had removed his right leg from the knee down.

His right eye was also hit by shrapnel. Ignoring the pain from his bleeding leg and injured eye, he took out his cellphone and called his family. Then, he waited for villagers to come and help him.

“I was lucky that I’d brought a phone with me, otherwise I could have died alone from excessive bleeding,” U Ba Shwe recounted. He’d gone into the forest, some four furlongs from his village, to collect vegetables, on September 8, 2022. He stepped on the landmine on his way back home.

Back then, the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army (AA) were fighting each other again. The two sides engaged in fierce fighting from late 2018 to November 2020 in Arakan State. Then after nearly two years of ceasefire, renewed hostilities broke out in August 2022.

According to research by DMG, 64 people died and 162 others were injured in explosions of landmines and unexploded ordnance (UXO) in 2022 in Arakan State and neighbouring Chin State’s Paletwa Township.

Before the mine blast, U Ba Shwe, a resident of Kun Ohn Su Village in Kyauktaw Township and the breadwinner of a six-member family, made a living collecting bamboo shoots in forests.

“I had never in my life thought that I would face a thing like this,” said U Ba Shwe.

His fellow villagers carried him on a stretcher to Yoetayoke cottage hospital. He reached the hospital in time, and his life was saved.

Nearly two weeks after he had lost one of his legs, U Ba Shwe had to flee his village, together with his family, as artillery shells fired by junta troops hit the village. They fled to Ponnagyun, and are still staying at a displacement camp opened at the town’s Ganan Taung railway station.

“I cannot work anymore. We are now dependent on donors,” said U Ba Shwe.

Forests are a main source of livelihood for people living in rural parts of Arakan State and Paletwa Township. Casualties from landmine encounters are all too common when foragers venture into the forests.

“I dread that I might step on a mine, but I have no choice because I don’t want to starve,” said U San Thein Maung from Shwepyi Village in Kyauktaw Township.

It has been more than five months since the AA observed a humanitarian ceasefire with the Myanmar military on November 26, 2022. Despite the truce, the risks posed by landmines and UXO continue to threaten local people.

Maung Kyaw Soe, a fifth grader from Khamaungseik village in Maungdaw Township, died on February 2 after stepping on a landmine. He was making a trap to catch birds near a bunker some 15 feet from the village police station.

“We have lost our son. Our fellow villagers have to go out and work for their livelihoods though they are concerned for their safety,” said Daw Aye Mar, the mother of Maung Kyaw Soe.

On March 1, U Aung San Htay, 38, from Zedi Pyin Village in Rathedaung Township, lost his left leg in a mine blast. He stepped on the landmine while on his way to the Mayu Mountains to collect bamboo. His right leg was also seriously injured.

Landmines and explosive devices hit the farmlands and forests where local people work. The lack of warning signs in areas where landmines and weapons are located, and the lack of knowledge about the dangers of landmines, are a challenge for local populations.

U Zaw Zaw Tun, executive director of Action for Community Resilience Organization (ACRO), which works to educate the public about landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERWs) in Arakan State, said that some organisations are working to raise awareness about the dangers of landmines and ERWs, but they are still weak.

“Mainly, there is still a small amount of landmine risk awareness in the area, and it is necessary to not only provide awareness, but also to do practical demonstrations up to the ground,” he added.

The Action for Community Resilience Organization (ACRO) said that there should be a strong trust-building effort between the military and the Arakan Army (AA) regarding the prevention and clearance of landmines that threaten people’s lives.

U Pe Than, a veteran politician in Arakan State, pointed out that the armed groups need to properly identify and resolve the landmines they have planted.

“If the armed forces take proper note of the landmines they have placed and deal with them, the risk of landmines will be removed for all,” he added.

Since February 2021, the military has been clearing landmines along the Sittwe-Ann road and on the left side of the highway from Angumaw Village to Khamaungseik Village in Rathedaung Township. After that, the military did not clear landmines anymore.

U Khaing Thukha, spokesman for the Arakan Army (AA), said at an online press conference on February 27 that the ethnic armed group is working to clear landmines and raise awareness in controlled areas in order to reduce the risk of landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERWs).

“For the safety of the people, the Arakan Army is working to reduce landmine explosions in the controlled areas,” U Khaing Thukha said.

Since November 26 — when the Arakan Army and Myanmar military reached an informal ceasefire — several people have been killed or injured in landmine explosions in Arakan State.

The Arakan Army criticised that the military regime’s forced returns of displaced people without guaranteeing their security during the cessation of hostilities is making it more difficult for the people.

The lives of those affected by landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERWs) and the families of those killed are still neglected, and support for rehabilitation is still weak.

“The lives of people injured in landmine explosions are completely ruined, and the families that depend on them become a burden,” said Wai Hun Aung, a writer and well-known philanthropist in Arakan State.

In July 2022, junta-appointed Minister for Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement Daw Thet Thet Khaing said that from fiscal year 2017-18 to present, K138.4 million has been provided to a total of 692 landmine victims at a rate of K200,000 per person, state-run media reported.

“Many jobs need to be created to facilitate the livelihoods of landmine victims, so that they can survive,” said Ma Khin Myint Zaw, director of the Arakan State-based Women Generation.

U Ba Shwe, who lost one leg and one eye in a landmine blast, is worried about his family’s future.

“If I go back home when stability and peace is restored in Myanmar, I don’t even know how to make a living with one eye and one leg,” he lamented.

.jpg)