- Over 200 IDPs in Ponnagyun struggle without shelter, food aid

- Junta airstrikes inflict deep psychological trauma on children in Arakan State

- Photo News: Over 200 IDPs in Ponnagyun in urgent need of shelter assistance

- Two children injured by UXO in Mrauk-U struggle to afford medical care

- High hepatitis cases hit children in Arakan State

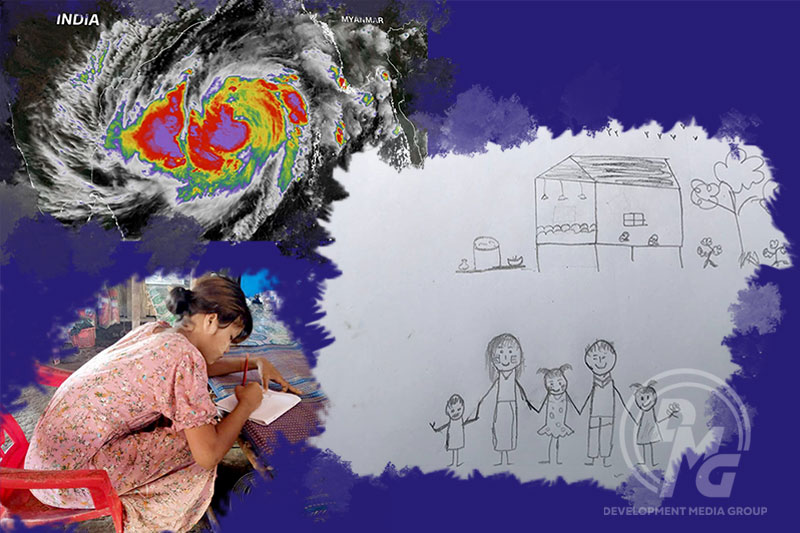

Cyclone Mocha: A Trauma for Many and for Children Especially

“My granddaughter has not talked to anyone for nearly two months. She has barely responded when I talk to her,” said Daw Sandar, Ma Akyaw May’s grandmother.

05 Sep 2023

Written By Myo Thiri Kyaw

It was a rainy, gloomy day. In a small room, a 13-year-old girl was drawing sketches under the dim light.

Scattered around her were coloured pencils and crumpled up papers. She was drawing a family.

Ma Akyaw May was born in Kyauktaw Township’s Pinnyawa Village. The ethnic Mro girl is the third of four siblings. But for the past four years she has been living at the Taungmin Kalar displacement camp, where she is taken care of by her grandparents, who are in their 70s.

Until about two months ago, Ma Akyaw May had always been described as a happy girl. Then Cyclone Mocha struck.

“My granddaughter has not talked to anyone for nearly two months. She has barely responded when I talk to her,” said Daw Sandar, Ma Akyaw May’s grandmother.

On May 13, one day before the storm made landfall over coastal Arakan State, more than 50 people including the elderly and children from Taungmin Kalar displacement camp evacuated to a brick religious hall in Taungmin Village.

The cyclone hit the village at around noon on May 14. They could see trees falling and roofs being ripped off around them. At approximately 2 p.m., they heard cracking sounds, and as they moved to another building at the opposite end of the religious compound, the building they were sheltering in collapsed.

“Less than three minutes after we were out of the religious building, it split in two. It happened right in front of the children. The children were so frightened, some burst into tears and some peed their pants. We had never seen anything like that before, except on television,” said Daw Ma Aye Khin from the displacement camp.

While the majority of displaced children who witnessed the scene have recovered both physically and mentally, the storm left a deep mental scar for Ma Akyaw May.

More than 1.5 million people in Arakan State’s Sittwe, Rathedaung, Ponnagyun, Kyauktaw, Mrauk-U and Buthidaung townships were affected by Cyclone Mocha, according to the military regime.

Children account for some 40 percent of the affected, according to social organisations and volunteers helping storm victims.

A higher prevalence of emotional trauma among children in rural areas and displacement camps in northern Arakan State has been reported in the aftermath of Cyclone Mocha, according to local civil society organisations providing emotional counselling for children.

“We can see insecurity and fear in their eyes,” said a member of a local civil society organisation providing emotional counselling in the aftermath of the storm. “They are suffering from different emotional trauma. Their parents are sad because their houses were damaged. It has an effect on the children. The fact that they have no shelter and food also makes children sad.”

Cyclone Mocha came as just the latest blow for children who have grown up amid the woes of war.

Ma Akyaw May’s parents, who live in the Taungminkalar displacement camp, divorced when she was about 5 years old. After her parents divorced, her four siblings were left with her grandparents in the village.

After that, Ma Akyaw May’s brother and three sisters were sent to an orphanage in Sittwe, according to the grandmother, Daw Sandar.

“I only adopted Akyaw May and sent the other three to an orphanage. Akyaw May was so young that she used to cry when her parents and siblings were gone, and I must say that she has been traumatised since she was young,” Daw Sandar said.

Ma Akyaw May’s family came to the Taungminkalar IDP camp along with the residents of the upper part of Kyauktaw Township after the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army (AA) started fighting in 2018. Ma Akyaw May grew up as the child of a divorced family, but she never resented taking care of the daily needs of her grandparents who lived with her.

“She is very clever. Even if we travel overnight, we can safely leave her alone at home. She also cooks rice and curry and is a clever student. She even won first prize in a painting competition,” Daw Sandar said.

Children’s rights include the right to health, education, family life, play and recreation, an adequate standard of living and to be protected from abuse and harm. Children are losing these rights in post-Cyclone Mocha Arakan State. Cyclone Mocha will without exception have been one of the scariest things to have occurred in the life of every child that lived it. Some children like Ma Akyaw May also say that rain and wind now scare them.

“Children are already in the grip of fear. When it rains and the wind blows, the children are afraid, and they ask where to run if there is a storm. The children cover their ears when it rains,” said Daw Cho Oo May, the mother of a child at Nyaungchaung IDP camp in Kyauktaw Township.

Psychologists have noted that a child whose parents can give them full love and affection can have a good future, and if they grow up traumatised, their success in life will be hindered. Parents worry that children who have experienced significant trauma will manifest that trauma developmentally as they grow.

“Children will always remember this incident in their minds. When they grow up, I only worry that they will be anxious and petty,” said the father of a child at an IDP camp in downtown Rathedaung.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has been working with partner organisations to increase mental health care for children in Arakan State still reeling from the effects of Cyclone Mocha. Fifty child-friendly spaces have been opened for trauma healing for children in Maungdaw, Buthidaung, Rathedaung, Sittwe, Pauktaw and Ponnagyun townships.

“We are healing the trauma of our children as much as we can. We listen to our children’s emotions. We provide entertainment for the children by drawing, singing, and telling stories,” a UNICEF official said.

Regarding the children’s trauma, parents of the children say that psychological healing is still not enough in some areas affected by the storm. In order to heal children’s trauma, there is an urgent need for international organisations, departmental entities and authorities, as well as parents, to create and heal, provide good communication and emotional support.

About 70 percent of the people affected by the storm are in need of emergency shelter and food. One of Ma Akyaw May’s wishes and hopes is to have a perfect family life.

“I want to stay with my parents,” she said. “I also remember my sister and brother. I also want some clothes.”

.jpg)