- Arakan Army signals willingness to forge strategic partnership with Bangladesh’s new government

- Internet blackout in Arakan State hampers emergency aid delivery

- Arakan residents call for air raid warning systems amid surge in junta airstrikes

- Arakan’s Breathing Space (or) Mizoram–Arakan Trade and Business

- Death toll rises to 18 after junta airstrike on Ponnagyun village market

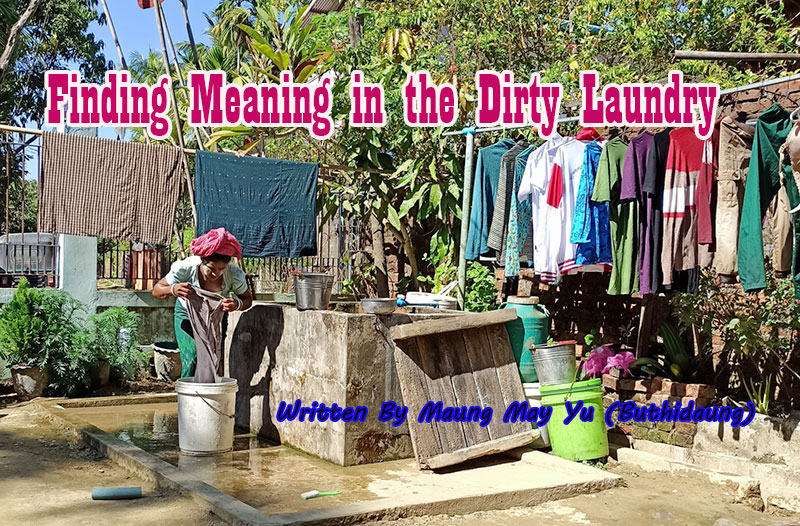

Finding Meaning in the Dirty Laundry

Ma Chan Myae Khaing, 24, is the mother of four children. She is also Hindu, and thus a religious minority in Arakan State’s Buthidaung Township, where she works as a laundrywoman for houses in Ywama village. She lives in the west of Ywama village and her name means “peacefulness,” but her life is not peaceful. Nonetheless, she is undeniably strong, overcoming myriad challenges in her life to be a good mother for her children.

16 Feb 2022

Written By Maung May Yu (Buthidaung)

A woman busies herself near a small pool. A basket of overloaded clothes, a bar of soap, a low stool and a large stone mat are waiting for her beside this pool. She pours some water from the pool into a small bucket. When the bucket is full, she sits down on the stool.

Then, she begins her daily washing routine. Working in the hot sun, she wraps a pink cloth around her head as a turban, but it cannot lessen the heat from the sun. She is soon drenched in sweat, but there is no time for rest as she moves from one house to another doing laundry.

Ma Chan Myae Khaing, 24, is the mother of four children. She is also Hindu, and thus a religious minority in Arakan State’s Buthidaung Township, where she works as a laundrywoman for houses in Ywama village. She lives in the west of Ywama village and her name means “peacefulness,” but her life is not peaceful. Nonetheless, she is undeniably strong, overcoming myriad challenges in her life to be a good mother for her children.

“I have a husband. But he is not reliable, and even makes trouble for us. He sometimes takes rice that I buy for the family, spending my earnings, and sells it to buy alcohol for himself. There are different kinds of sufferings I face from a bad husband,” said Ma Chan Myae Khaing.

She was born to poor parents. At the age of 16, she found a boyfriend and followed him as she believed in him. After they were married, she says her husband, a casual labourer, changed.

A growing dependence on alcohol was excused by her husband as stemming from the hardships of his work life. After having three children year by year, her husband had become an alcoholic, according to Ma Chan Myae Khaing, who said these days he drinks away all the money he earns, and never takes care of the family.

Ma Chan Myae Khaing has had to work since her husband went down that path. She has no education. As they had no capital and few friends, she decided to pursue a career in the laundry business, which is easy to get a job.

She does laundry from house to house all day, almost every day, and all her earnings are spent to buy food for the family. Eggs and dried fish are common meals for her family. When she arrives at home, her husband is waiting to ask for money to buy alcohol. If she cannot find the money, she faces a row with her husband; sometimes she is beaten by her husband. However, she puts up with him for her children’s sake.

There is a saying among Myanmar people: “Three things are difficult to repair; getting married, building a pagoda and getting a tattoo.” As the saying goes, one needs to consider carefully before getting a tattoo, before building a pagoda, and before getting married, to be sure not to make a mistake. Ma Chan Myae Khaing is now regretting her marriage at a relatively early age.

“I’d like to urge girls not to get married at such a young age that you cannot know about the world entirely,” she says.

She is trying to make the best of her life considering that which can’t be changed. From the time she couldn’t rely on her husband, she became head of the family. Most people see only men as the head of a family. This story is not that story.

Many families are headed by wives who are smarter than their husbands. In Ma Chan Myae Khaing’s case, she is not only the head of the family but also a wife who is doing the work.

“There are four children at home and one husband. The eldest son is 7 years old. The youngest son is 3 years old. I am the only one who is responsible for their livelihood,” she tells DMG. “There are uncomfortable days. Sometimes, I feel regret about my life. But it cannot be solved by just feeling regret. If I do not work, my children will starve.”

Her family needs more than a bag of rice a month and it spends at least K50,000 on food alone. She has to work hard to get that amount of money in a month. If she cannot earn enough money, her family will starve. Thus, she has to go from house to house doing laundry, rain or shine.

She works for three houses where she earns a monthly income. Each house pays K30,000 per month. Her monthly salary is enough for her family to eat — if she can work regularly. But she is worried about how any future resurgence of the Covid-19 pandemic could affect her business.

“I faced a lot of trouble during the previous [third wave] wave of Covid-19. I couldn’t do laundry at that time because I wasn’t allowed to enter houses. So, I couldn’t earn money and faced troubles. At the time, commodity prices were rising. So, the condition deteriorated. I heard the Omicron variant is spreading now. I am worried about my business,” she said.

Her worry reflects how much trouble her family faced during the last Covid-19 outbreak. People like Ma Chan Myae Khaing, along with internally displaced people (IDPs), arguably suffer the most during that time. At present, the Omicron variant has spread globally, including to Myanmar.

Ma Chan Myae Khaing is only 24 years old, but she looks at least 30; such is the burden of household responsibility under such circumstances. She uses her strength to provide not only for her children but also for her wayward husband. She still smiles and carries on, showing the power of a woman.

Ma Chan Myae Khaing offers a message to young women out there, hoping they can avoid the trouble that she is now embracing.

“Girls should study something at a young age, whether it is in school or in a professional career. And they should avoid getting married during their teenages, and they should decide with their brain when they are going to get married, at the right time.”

.jpg)