- Weekly Highlights from Arakan (Feb 23 to March 1, 2026)

- Over 300 political prisoners freed from 10 prisons nationwide

- DMG Editorial: Between War and Opportunity - A New Border Reality for Bangladesh and Arakan

- Arakan Army sets five-year prison term for kratom cultivation in controlled areas

- Junta airstrikes kill over 25, including Arakanese merchants, in Mindon Twsp

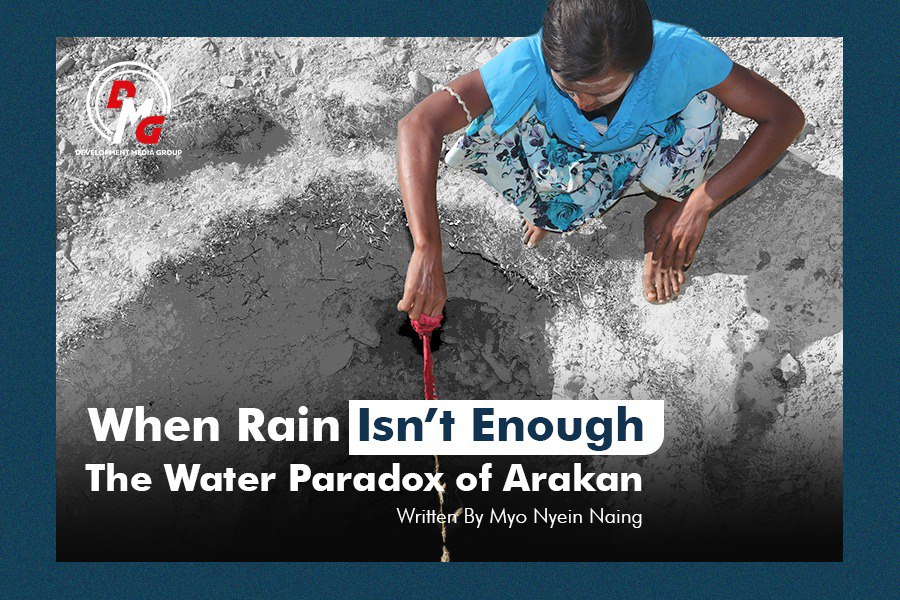

The Water Paradox of Arakan: When Rain Isn’t Enough

It’s a crisis that defies intuition. How can a place so abundant in rainfall be perilously dry for months every year? The answer lies not in the clouds but on the ground: a catastrophic failure of infrastructure, compounded by civil war and a vacuum of accountable governance.

02 Dec 2025

Written By Myo Nyein Naing

In the wettest corner of Myanmar, people are dying of thirst.

This isn’t a metaphor. Arakan (Rakhine) State, on Myanmar’s western coast and drenched with more than 200 inches of rain each year, is now the epicenter of a devastating water shortage. Last summer, nearly 80 people died not from bullets or bombs, but from waterborne illnesses—direct consequences of lacking safe drinking water.

It’s a crisis that defies intuition. How can a place so abundant in rainfall be perilously dry for months every year? The answer lies not in the clouds but on the ground: a catastrophic failure of infrastructure, compounded by civil war and a vacuum of accountable governance.

I’ve seen images that never reach international news: long lines of women and children waiting with containers for a daily ration from humanitarian groups. Many are among the more than 600,000 people displaced by fighting between the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army (AA), which now controls most of the state. These displaced populations have crowded into rural areas, straining ponds and wells designed for a fraction of today’s demand.

Here’s the hard truth: this is not primarily an environmental problem. It is a political one. Monsoon patterns may shift year to year, but scarcity has become a predictable tragedy. The rain simply runs away. We lack reservoirs, treatment plants, and piped networks to capture abundance and carry communities through the lean months.

For decades, the national government in Naypyidaw neglected Arakan. A National Water Policy promised equitable access and integrated management, but investment rarely materialized, especially in a region treated as political periphery. Corruption and bureaucracy stifled progress, leaving communities reliant on shallow, unprotected ponds that become breeding grounds for disease when they stagnate and shrink.

War has collapsed what little existed. The national government has retreated, and the AA—effective at seizing territory—is not a public utility provider. Its focus, inevitably, is on the battlefield, not on building water systems. The result is deadly. Current authorities lack the technology and finance to manage water at scale, and millions are caught in the middle.

So, what can be done?

First, stop treating this as a natural disaster and start treating it as a man-made one. That reframes the solution from waiting for rain to demanding accountability and investment.

Second, while a political settlement is essential, people cannot drink diplomacy. As the de facto authority in much of Arakan, the AA must be encouraged and supported to prioritize civilian life: facilitate and protect humanitarian access, keep existing water sources functioning, and begin building simple, resilient storage.

Finally, international and community-based organizations must shift strategy. Trucking water is a vital stopgap, but not a solution. Aid should build local capacity and fund sustainable, community-managed infrastructure—rainwater harvesting, protected springs, basic treatment—designed to operate even amid conflict.

The people of Arakan are not asking for a miracle. They are asking for the means to capture the rain that already falls so generously on their land. Ensuring access to safe water is more than a humanitarian act; it is the foundation for any future peace and stability. A child who dies from diarrhea is as much a casualty of war as a soldier felled in combat. Until we address the water crisis, we are treating symptoms while the disease of political failure continues to claim lives.

About the author: Myo Nyein Naing is a university student majoring in Quantitative Economics at St. Olaf College in the United States.

.jpg)