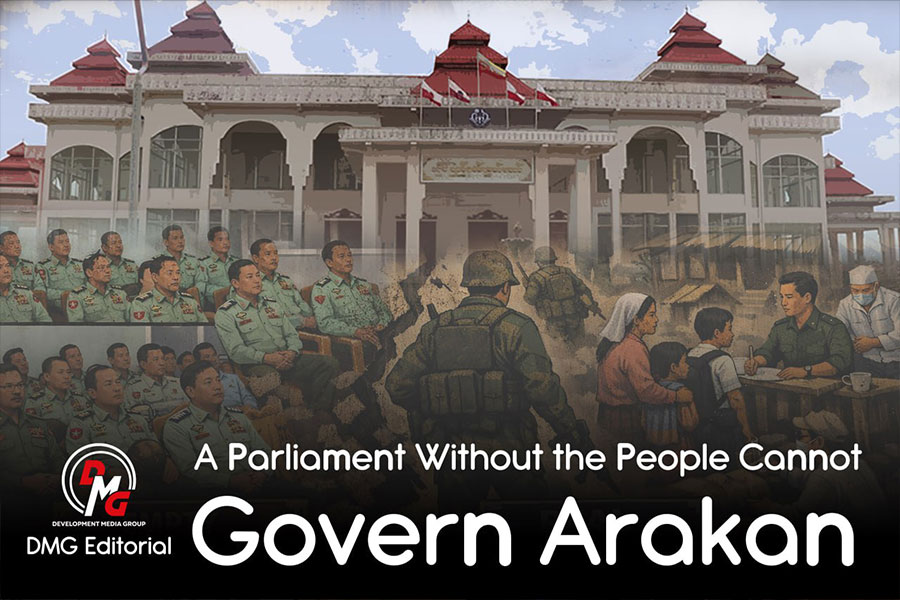

- DMG Editorial: A Parliament Without the People Cannot Govern Arakan

- Displaced Arakanese struggle to rebuild homes leveled by junta airstrikes

- India suspends Arakan trade route for two months after death of truck driver in Paletwa

- Landmine, ERW casualties rising in Arakan State amid ongoing conflict

- Eight children killed or injured in two days of shelling, UXO blasts in Hpakant

DMG Editorial: A Parliament Without the People Cannot Govern Arakan

A parliament without the consent of those governed becomes symbolic at best and irrelevant at worst. Political legitimacy does not come from seat allocation formulas or amended election laws; it comes from who the people recognize as governing their lives.

17 Feb 2026

Arakan today is governed by war, not by ballots. Any discussion of a future Arakan State Parliament that ignores this reality risks becoming an exercise in political fiction.

On paper, the military regime is preparing to convene a state parliament in 2026, following elections held in just three of Arakan’s seventeen townships. In reality, most of Arakan is no longer governed by the military regime at all. Large areas are administered by the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA) through the People’s Revolutionary Government of Arakan (PRGA), which has established functioning civilian systems in administration, health, education, justice, and local governance.

This is not an abstract claim. It is the daily experience of millions of people across Arakan.

Clinics operate under PRGA authority. Schools function outside the junta system. Local disputes are resolved through parallel courts. Civil administration, taxation, and local order are enforced not from Naypyidaw, but by Arakanese authorities on the ground. Whatever one’s political position, one fact is undeniable: real governance in much of Arakan already exists outside the framework of the proposed state parliament.

Against this backdrop, the recently concluded election raises more questions than answers.

Voting took place in only three townships, Sittwe, Kyaukphyu, and Manaung and even there under severe restrictions. Just over 100,000 votes were cast in a state of more than 3.1 million people. Entire regions were excluded outright, not because of voter apathy, but because conflict and territorial realities made elections impossible.

Rather than acknowledging this breakdown, the military regime responded with electoral engineering: blending first-past-the-post and proportional representation to assign parliamentary seats to townships where no votes were cast and where MPs cannot physically travel.

This leads to a fundamental question that no legal amendment can erase: Who do these MPs represent?

They do not represent voters, because voters were absent. They do not represent communities, because they cannot reach them.They do not represent governance, because parallel civilian systems already operate independently of them.

The contradiction is now sharpened by events on the ground. Fresh armed clashes in Kyaukphyu and Sittwe, towns used to justify the election’s legitimacy have once again exposed how fragile the security situation remains. Civilians continue to face displacement, restricted movement, and fear. Markets are disrupted. Roads are unsafe. War does not pause for parliamentary schedules.

In such conditions, the idea of a functioning state parliament becomes increasingly detached from reality. A legislature is not merely a chamber with chairs and microphones. It requires constituency access, public consultation, political consent, and trust. None of these can exist when representatives cannot safely enter their constituencies or engage with the people they are meant to serve.

More importantly, Arakan is now living under two political systems occupying the same space. One exists in official announcements, gazettes, and planned parliamentary sessions. The other exists in villages, towns, schools, clinics, and local courts. One speaks the language of constitutional procedure. The other governs daily life.

A parliament that ignores this reality does not unify Arakan, it deepens the disconnect.

Representation without people is not representation. A parliament without the consent of those governed becomes symbolic at best and irrelevant at worst. Political legitimacy does not come from seat allocation formulas or amended election laws; it comes from who the people recognize as governing their lives.

The deeper danger is that this parliament may become a substitute for political dialogue rather than a platform for it, a structure designed to project normalcy while avoiding the harder truth that Arakan’s political future cannot be resolved through procedural shortcuts under conditions of war.

The question, therefore, is not whether the Arakan State Parliament can be convened.

The real question is this: Can a parliament that excludes the majority of the population, ignores parallel civilian governance, and operates amid active conflict genuinely represent Arakan?

Until political processes reflect the realities on the ground, who governs, who delivers services, and who the people actually turn to for authority, any parliament formed under current conditions will struggle to be more than a performance.

For the people of Arakan, representation is not theoretical. It is measured by safety, access, dignity, and voice. A parliament that cannot answer to those standards will not shape Arakan’s future. It will merely sit beside it.

.jpg)