- IDPs in Kyauktaw struggle with collapsing shelters amid aid shortages

- Travel restrictions deny Arakanese youth access to higher education

- Motorists fined K30,000 for traffic violations in AA controlled areas

- Inmates escape from Kyaukphyu Prison amid heightened security

- Arakan farmers struggle as paddy market collapses, debts mount

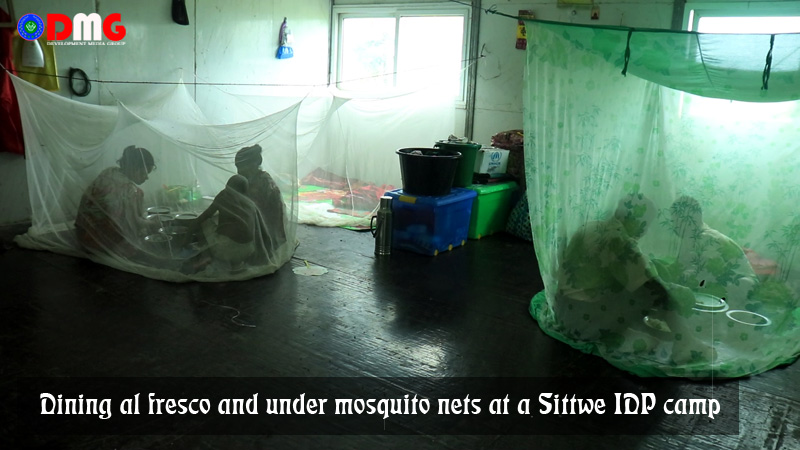

Dining al fresco and under mosquito nets at a Sittwe IDP camp

A mosquito net is normally an accessory to protect sleepers from the bites of mosquitoes and other insects, but at a camp for internally displaced people (IDPs) in the Arakan State capital Sittwe, it is more than just that.

30 Aug 2020

By Min Tun | DMG

A mosquito net is normally an accessory to protect sleepers from the bites of mosquitoes and other insects, but at a camp for internally displaced people (IDPs) in the Arakan State capital Sittwe, it is more than just that.

Each day at around noon, four or five people can be seen within the confines of one of these nets, draped over them like a supersized bridal shroud. But this is no wedding, nor are the enshrouded sleeping.

It’s lunchtime for these IDPs, who prefer to have their meals without the accompaniment of the flies that will surely pester them if given the opportunity.

Their camp is within the compound of the Maha Zeya Theikdi Pahtan Monastery, located just a 10-minute drive from the seat of state government in Sittwe, where the chief minister and his cabinet work.

On a recent day at the IDP camp, 38-year-old U Kyaw Win Hlaing, a father of three, is having lunch with his family under the mosquito net.

For him, the flies are more than just a nuisance; he says they are one component of unsanitary conditions at the camp that he blames for his daughter’s health problems.

The mosquito net prevents the flies from alighting on the food going into his family’s stomachs, he said.

“Flies are spawned from the rubbish dump. A lot of flies come when we have food. So, we have to eat lunch inside the mosquito nets,” he explained.

More than 50 people from Kyauktaw, Rathedaung and Paletwa townships are taking shelter at the Maha Zeya Theikdi Pahtan Monastery.

U Kyaw Win Hlaing arrived at the monastery with his wife and children in February. They hail from Pyaing Taing village in Kyauktaw Township, and at about the six-month mark of their time at the camp, their 3-year-old daughter came down with diarrhoea.

U Kyaw Win Hlaing believes his daughter suffered from the illness due to the flies that come from the rubbish dump — the stench of which can be smelled from the monastery. His daughter is better now, but even in recovery she has to visit Sittwe General Hospital once a week to get more medicine.

IDPs in the camp, both children and adults, report suffering from diarrhoea frequently, with many in need of financial assistance in order to afford a trip to the local health clinic, U Kyaw Win Hlaing said.

“We are refugees and we do not have money because we cannot work. If we visit a clinic in the ward, we need money. So, we want people to provide money for our medical expenditure,” he said.

If the flies and stench from the rubbish dump were not enough, another smell also challenges IDPs’ staying power: the foul odour emanating from an active crematorium at the nearby cemetery.

Buddhist monk Ashin Kaw Wi Da, who manages the camp, said some IDPs relocated to other places because they could not stand the stench and flies. Dozens remain, however, enduring these challenges with repurposed mosquito nets and other adaptations intended to make their hardscrabble lives a little easier.

Many of those left at the monastery are impoverished, or are families who worry about the hassles of moving to another IDP settlement with children in tow, the monk added.

U Kyaw Win Hlaing says his family cannot relocate. His second daughter is less than 3 years old and their youngest, a baby boy, is just 8 months old.

“If we move to another place, we’ll need food and clothes. My children are too young and it is difficult for them to move from one place to another,” he said.

IDPs like U Kyaw Win Hlaing and his family were displaced from their homes for a variety of conflict-related reasons, whether due to clashes nearby, artillery shells landing within villages, or the torching of homes.

The Rakhine Ethnics Congress has estimated the number of IDPs in Arakan State to be about 200,000. Hostilities between the Tatmadaw and Arakan Army that began in December 2018 have escalated in the months since, adding tens of thousands to the ranks of the displaced.

IDPs commonly face hardships securing adequate accommodation and food, or accessing healthcare and education.

The IDPs at Maha Zeya Theikdi Pahtan Monastery in Sittwe have been fortunate so far to not have to worry about empty stomachs, with the monastery providing food for them.

Decent healthcare has been lacking for the monastery’s IDPs, but the local Health Department recently told them that healthcare services would be provided at the camp once a week beginning this month.

That’s an improvement, but as U Kyaw Win Hlaing would no doubt be happy to point out, the flies and stenches remain. For now, it’s dining al fresco and under a mosquito net for him and his family.

Places like the Maha Zeya Theikdi Pahtan Monastery are a temporary place to shelter, and that notion of impermanence can be sustaining amid daily hardship.

But here and at many IDPs camps across Arakan State, it is the status of a conflict with no end in sight that will determine when they return to their homes.

“I want the war to be stopped,” U Kyaw Win Hlaing said. “But I cannot demand it because the war has intensified and my wish alone cannot end it.”